HISTORY

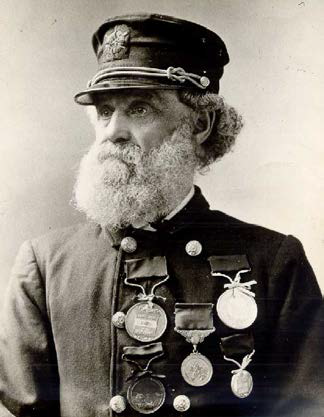

Captain Joshua James, USLSS 22 November 1826 - 19 March 1902

Captain Joshua James, USLSS 22 November 1826 - 19 March 1902

"Here and there may be found men in all walks of life who neither wonder nor care how much or how little the world thinks of them. They pursue life's pathway, doing their appointed tasks without ostentation, loving their work for the work's sake, content to live and do in the present rather than look for the uncertain rewards of the future. To them notoriety, distinction, or even fame, acts neither as a spur nor a check to endeavor, yet they are really among the foremost of those who do the world's work. Joshua James was one of these." [Quote by the Superintendent of the U. S. Life-Saving Service, Sumner Kimball]

Joshua James was probably the most celebrated lifesaver in the world, credited with saving hundreds of lives from the age of 15 when he first joined the Massachusetts Humane Society until his death at the age of 75 while on duty with the U.S. Life-Saving Service. He was honored with the highest medals of the Humane Society, the United States, and many other organizations. His father, mother, brother, wife, and son were also heroic lifesavers.

Joshua James was the ninth of twelve children. He was called a "great caretaker" by his brothers and sisters. He was reared by his older sister Catherine, who tended him from babyhood and took over the family upon the death of their mother. Her death was the first tragedy of Joshua's life. She and Joshua's baby

sister perished in the sinking of the schooner Hepzibah, belonging to Reinier, her son and one of Joshua's older brothers. This event was influential in shaping Joshua as a lifesaver.

A natural seaman, Joshua also applied himself to practical books, and started going to sea early in life with his father and brothers. One night when the helmsman lost his bearing in unfamiliar waters, Joshua was roused from a sound sleep and brought on deck. Yawning and with half-opened eyes, he scanned the heavens, laid down a course, remarked that a certain light would be sighted in two hours, and went back to bed. The light was sighted one hour and 55 minutes later. On another occasion Joshua was sailing a yacht in dense fog, all bearings apparently lost. Someone asked him where they were. He replied "We are just off Long Island head." "How can you tell that?" he was asked. "I can hear the land talk," he answered.

His profession was hauling, lightering, and freight carrying, like his father and brothers. He went into business at the age of 25 and remained until he was 62, when he became a full-time lifesaver with the U.S. Life-Saving Service. His wife, Louisa Luchie, was born when he was but 16 years of age. Joshua waited for her to grow up and proposed when she reached the marriageable age of 16. Two years before she had saved the life of a swimming companion--establishing a tradition of lifesaving that ran through both their lives and their families. Their children numbered eight girls and two boys. Three of the girls and one boy died in infancy, saddening the father for the rest of his life. The surviving son, Osceola James, born in 1865, became a sailor, master of the Myles Standish, a captain of the Hull volunteer life-savers, a gold lifesaving medal winner with a record approaching his distinguished father's. Home life in the James' household centered around the family orchestra (James was a consummate musician), good books, chess, and checkers.

Joshua's lifesaving activities began when he was 15 years of age, when he participated in a rescue in one of the Massachusetts Humane Society lifeboats at

Hull. The wreck at Harding's Ledge was in early 1842. Unfortunately no details are available--indeed, many of his rescues are lost to history due to a fire at the Massachusetts Humane Society headquarters that destroyed many of their early records.

We do know about a few of these earlier rescues. He was awarded a bronze medal on 1 April 1850 for the rescue of the crew of the Delaware on Toddy Rocks. In 1864 he helped rescue the crew of the Swordfish. In 1871 he helped in the rescue of a schooner. In 1873 he helped with the rescue of the crew of the Helene. In 1876 he was appointed keeper of 4 Massachusetts Humane Society life-boats at Stony Beach, Point Allerton, and Nantasket Beach. On 1 February 1882, Joshua and his crew of volunteers launched a boat in a very heavy gale and thick snowstorm to rescue the crew of the Bucephalus, and also on the same day they rescued the crews of the Nellie Walker.

An exciting rescue was that of the crew of the Anita Owen on 1 December 1885. It was midnight, dark, with a northeast gale blowing a thick snow. Joshua and his crew got to a wrecked vessel under hazardous conditions, and found ten persons on board. They could only take five at a time. The captain's wife was taken off first, then four others in the first load. On the trip to the beach the boat was hit by a huge wave and filled, but everyone reached shore. The second trip was more dangerous. The steering oar was lost and wreckage was all about. Nevertheless they managed to get the remaining five crewmen ashore. On 9 January 1886, Joshua and his men rescued the captain of the Millie Trim, but were unable to save the rest of the crew.

A special silver medal was struck for Joshua by the Humane Society in 1886, for "brave and faithful service of more than 40 years." The report said "During this time he assisted in saving over 100 lives."

The most famous rescue of his career, for which he received the Humane Society's gold medal, as well as the Gold Life-Saving Medal from the United

States Government, took place between the 25th and 26th of November, 1888. During that period he and his men saved the lives of 29 persons from five vessels.

The official report on his 1888 rescues that earned him the Treasury Department's Gold Lifesaving Medal

The storm of this event was the greatest known in Hull, sweeping the Atlantic coast from the Carolinas to Maine. Early in the morning of the 25th, Captain James and a few of his beachmen climbed to the top of Telegraph Hill for observation, and saw several schooners through the blinding snow. Joshua knew they could not withstand the storm, so he alerted his crews and ordered a beach patrol starting at two in the afternoon. Hardly had it begun when the three-masted Cox and Green was found broadside on the beach. Nine men were removed by breeches buoy.

The second three-masted schooner, the Gertrude Abbott, was found an eighth of a mile further up the beach just as the first rescue was completed. It was dark now, and this vessel was too far from the shore to use the breeches buoy, and rescue by lifeboat was so dangerous that Joshua asked for volunteers from his volunteer crew -- warning that chances were they would never return from the attempt. All were willing to go with him. People gathered and built a great bonfire on Souther's Hill, assisting the boat's crew. The boat was filled by every wave -- and two men were kept busy bailing. They got to the vessel and the eight stranded sailors dropped one by one into the rescuers outstretched arms. Getting back to shore was the hardest part. The large crowd on shore watched the desperate struggle, cheering one moment, gasping the next. Two hundred yards from shore the boat struck a boulder and rolled under water--but the crew shifted weight and saved the boat. But a monster wave lifted it high and smashed in on the rocks. All the men managed to reach the hands of the crowd, which rushed

into the surf to assist them. At nine o'clock all were safe ashore. Joshua and his men resumed their patrol of the beach on foot.

At three in the morning they found the third three-master schooner, the Bertha F. Walker. They had to go four miles for a boat to replace the one lost. The boat was a new untested one designed by Joshua's brother Samuel. (It was an axiom of the service that lifesavers might fail in an unfamiliar boat even though it was a better boat. This added greatly to the danger.) However, they rescued the seven survivors without mishap.

While the third rescue was still in progress, a messenger on horseback arrived with news of two more wrecks at Atlantic Hill. Two other lifesaving crews were on the scene, and they handled one of the cases. They had tried unsuccessfully on the other -- the H.C. Higginson, with five men in the rigging. Joshua and his men launched their boat and struggled desperately for 45 minutes, only to be washed back ashore with two holes stove in the new boat. They patched the boat and tried again, this time reaching the vessel. With difficult maneuvers and great suspense they got the five men into the boat. The body of the steward had all the time been bound to the topmast, and they could not remove him, so it remained overlooking the scene. Captain James and his men then got their first rest in 24 hours after they completed the fourth rescue.

James described the rescue in an official interview soon after the event.

From his account it can easily be seen that Joshua James was in the boats on all five trips; that Osceola James, Alonzo L. Mitchell, John L. Mitchell, and Louis F. Galiano were in four of the five boat crews, and the eighteen others in trips of lesser number. It is also noteworthy that four James, four Galianos, and ten Mitchells were members of these crews.

The damage resulting from this storm emphasized the need of additional government life-saving stations, with full equipment and drilled and paid crews, along the coast. It was natural that a station should be established in the vicinity of Hull and one was so established in 1889 at Stony Beach and was named the Point Allerton station. When it came to the selection of a keeper there was no doubt who was to be the man. On 22 October 1889 Joshua James took the oath of office as keeper of the U.S. Life-Saving Station at Point Allerton (he's on the right in the photo at the station's boathouse, circa 1895). He was, however, 62 years of age, which was seventeen years past the maximum age limit for a federal appointment with the new U.S. Life-Saving Service, but an extraordinary exception was made in his case and this requirement was waived. At 62 and eleven years later at 73, Joshua passed all of the physical examinations with no difficulty. For the record, under past experience qualifying him for the position, Joshua wrote "fisherman." Captain James selected his crew of seven men from men from Hull and during the thirteen years he as keeper of the Point Allerton station, he and his crew saved 540 lives and $1,203, 435 worth of estimated value of ships and cargo.

An unusual rescue was made on 16 December 1896 when the three-masted schooner Ulrica was wrecked in a northeast gale and a thick snowstorm three miles south of the Point Allerton station. Joshua engaged a local farmer and two horses to rush the boat to the scene. The trainmaster of the electric train from Boston, hearing of the emergency, put the train at the service of the life-saving crew and rushed them to the scene. The schooner was 500 yards offshore. On the first two tries, the boat was thrown back on the beach. On the third try Joshua was thrown from the boat. The boat passed over him. He came up, grabbed the end of an oar, and was dragged back to shore with the boat. Realizing that he could not get the boat out, Joshua took command of the beach apparatus. A line was fired to the ship and secured, but it was too low for a breeches buoy. Joshua and his men got back in the boat and used the rope as a trolley line to pull

themselves out to the vessel. The stranded sailors were so numb with cold that one of the lifesavers had to climb on board and help them off the schooner.

The crowning achievement of Joshua's career was the rescue work in the storm of November 1898. The storm was even worse than the one in 1889. On the morning of 27 November Joshua and his men rescued two survivors of thirteen men in two vessels dashed upon Toddy Rocks. Then they took in a family whose home was threatened by the storm. Next, by breeches buoy, they removed seven men from a three-masted schooner. After that they fought their way to a barge in the surf and rescued five men. All that night they kept a constant patrol. The second day they rescued three men from a schooner, then three men from Black Rock. For 48 hours they were engaged in continuous rescue work. Joshua said of the storm "We succeeded in getting every man that was alive at the time we started for him, and we started at the earliest moment in each case."

The dramatic death of Joshua James occurred on 19 March 1902. Two days earlier the entire crew save one of the Monomoy Point Life-Saving Station perished in a rescue attempt. This tragedy affected Joshua deeply, and convinced him of the need for even more rigid training of his own crew. So at seven o'clock in the morning of 19 March, with a northeast gale blowing, he called his crew for a drill. For more than an hour, the 75-year-old man maneuvered the boat through the boisterous sea. He was pleased with the boat and with the crew. Upon grounding the boat he sprang onto the wet sand, glanced at the sea and stated, "The tide is ebbing," and dropped dead on the beach.

With a lifeboat for a coffin, Joshua was buried, and another lifeboat made of flowers was placed on his grave. His tombstone shows the Massachusetts Humane Society seal and bears the inscription "Greater love hath no man than this -- that a man lay down his life for his friends."

Captain Joshua James' funeral cortege.